Blissful UI Development with SwiftUI and Godot.

Xogot is a SwiftUI interface built on top of the Godot engine. To speed up development, we needed a way to build large portions of the user interface without having to compile and deploy the entire project every time.

A full build of the app in Godot takes a couple of minutes, and launching Xogot on the iPad with a new project adds another 20–30 seconds. That’s far too slow for quick UI iteration.

Our goal was to develop and refine UI components quickly, without starting up the entire Godot engine each time. This post explains the approach we settled on.

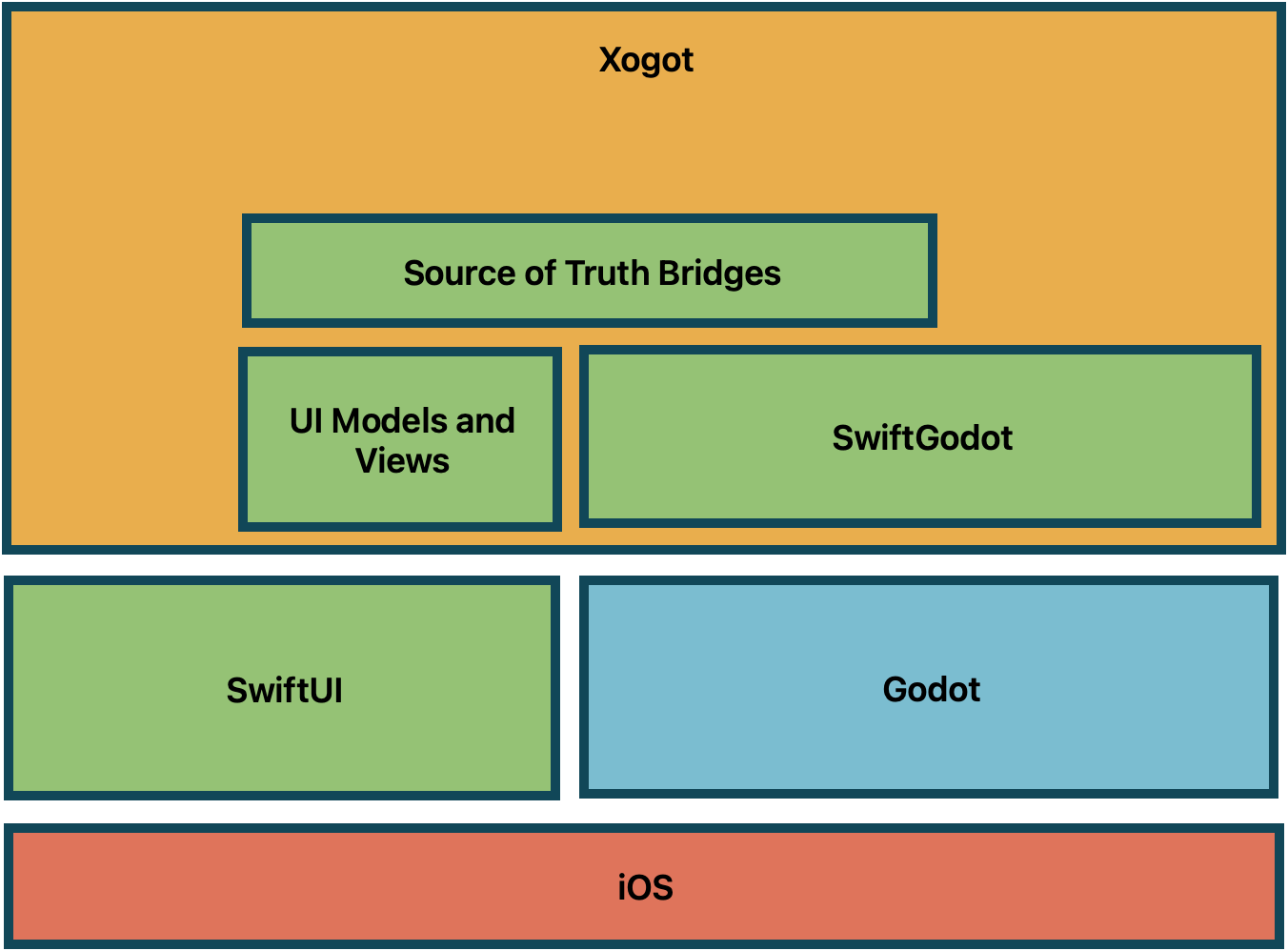

Project Structure

Xogot is organized roughly like this:

SwiftUI previews are perfect for rapid UI iteration, so we keep components small and modular. In production, these components connect to Godot, receive updates from it, and update Godot when the user interacts with them.

This was a very organic process, as we started with humble goals “Let us just make the ScenePad native”, and later that became “We really need the Inspector too”, and next thing we know, we had fallen down the slippery slope of rewriting most of the UI.

Due to this organic process, we came up with ad-hoc solutions for each module, one by one, one for the scene pad, then one for the file pad, then one for the selection, the one for dialog boxes and on and on.

Over time, this ad‑hoc approach became inconsistent, as each component had their own way of doing things. After a lot of trial and error, we arrived at a clean, reusable pattern that we have since deployed, and I wanted to share it with you.

Our Pattern

In Xogot, Godot always holds the source of truth—whether that’s the current scene, object selection, or plugin data. For example, an AnimationPlayer contains animation data, tracks, keyframes, and effects; a TileMap contains tile information, and so on.

We needed a way to expose Godot’s state to SwiftUI so SwiftUI could react to changes in real time, and user actions in the UI could push changes back to Godot. Neither SwiftUI’s @State or @Binding was exactly a match for this - but it turns out that the new @Observable system was exactly what we needed. And in retrospect, without it, we would not have been able to build Xogot, let alone, be in a position to sanely maintain it.

The @Observable system in SwiftUI is incredible. You flag a class as @Observable, and then you write your SwiftUI code in a way that relies on that data - but you do not have to do any bookkeeping on your own. The @Observable is the bookkeeper.

We use this extensively for very sophisticated user interfaces that merely rely on the data to render themselves. Then, as the data changes, the UI is updated accordingly. Once you make this leap, you never want to deal again with keeping track and state yourself in your UI.

My estimation is that the @Observable macro is responsible for cutting in half the amount of UI code that is necessary to display complex UI elements compared to the C++ code, while allowing us to do more than the original C++ code does, and opening the doors for doing even more with a trivial amount of work.

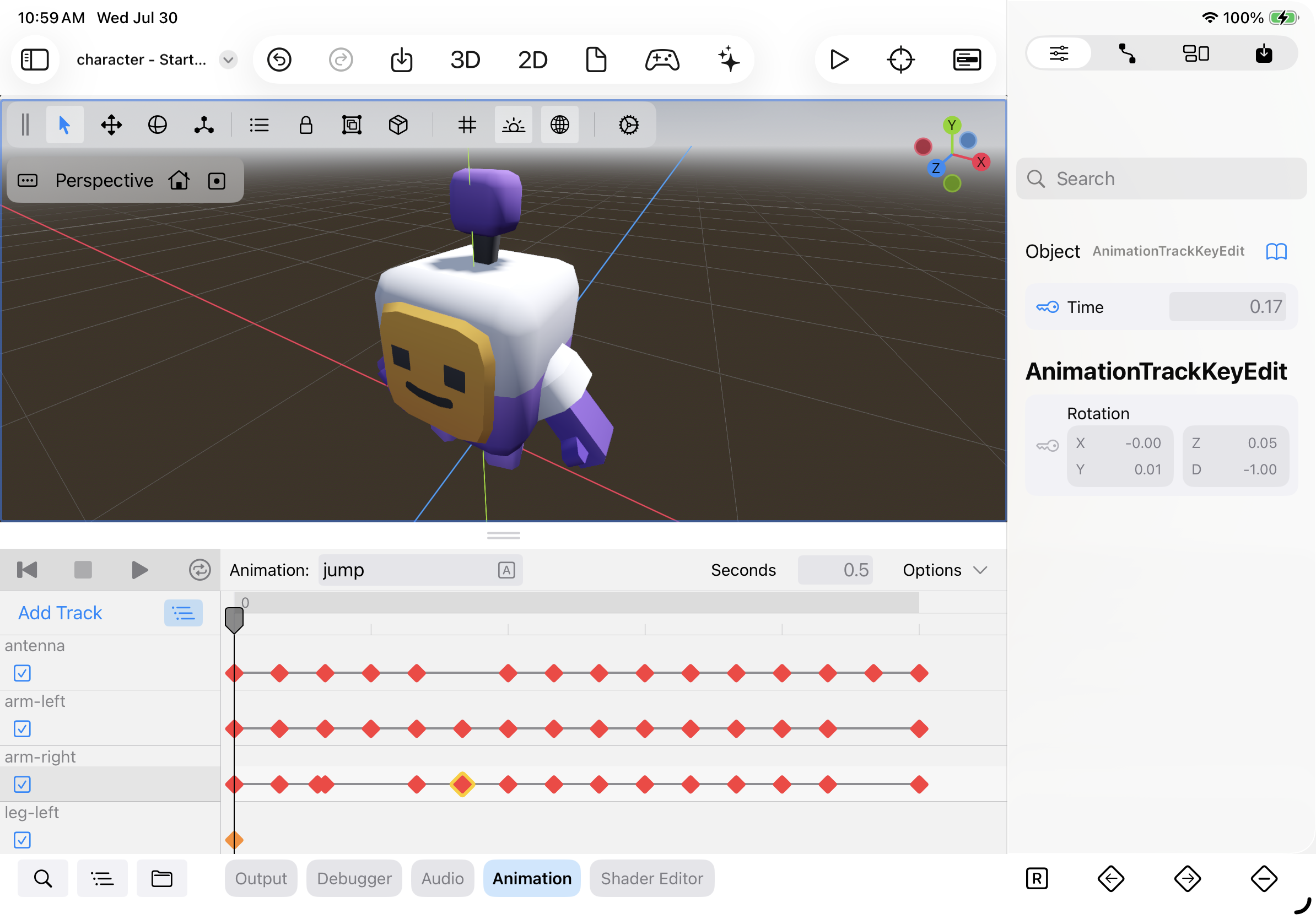

The following models show what we did for implementing the Animation Pad view:

Building and Testing without Godot

For each Godot data type, we create a SwiftUI Observable model. Here’s a simplified example for a Godot “Animation”object:

@Observable

open class AnimationModel: Identifable, Hashable {

/// Name for this animation

public private(set) var name: String

/// Tracks contained in this animation

public private(set) var tracks: [AnimationTrackModel] = []

/// Duration of the animation In seconds

public private(set) var length: Double

/// The current time position in seconds

public private(set) var timePosition: Double

/// Whether the player is currently playing

public private(set) var playing: Bool

open func setLength(_ value: Double) {

length = value

}

open func setTimePosition(_ position: Double) {

timePosition = timePosition

}

open func optimizeAnimation() {

// This needs to be implemented later

}

}Then, we build SwiftUI views around these models. For example:

// This is not real code, but illustrated how it is used

struct AnimationModelView: View {

@State var animationModel: AnimationModel

var body: some View {

// Do somethign interesting with it

VStack {

RenderTimeline(timePosition: $animationModel.timePosition)

RenderTracks(animationModel.tracks)

Button("Set Animation Duration to 1 second") {

model.setLength(1)

}

Button("Move animation to 0") {

model.setTimePosition(0)

}

}

}

}To test the above, we create dummy implementation of the AnimationModel that work on local data. Then we can iterate and develop those elements locally without having to launch Godot at all and using SwiftUI previews to prototype and iterate on the look and feel.

You will notice that I made it so that the properties were not directly mutable, and instead I provided methods to make changes to them - this is done so that I can hook the implementation that will communicate changes in the model back to Godot.

Integrating Back into Xogot

Once a component is ready, we integrate it into Xogot, which links with Godot. This is where we pay the build and integration tax.

The Xogot code that glues Godot with the UI code then creates subclasses that implement the bidrectional communication between these observable objects and the Godot source of truth.

class XogotAnimationModel: AnimationModel {

// This points to the Godot Animation, which is exposed via SwiftGodot:

var godotAnimation: SwiftGodot.Animation

init(godotAnimation: SwiftGodot.Animation) {

self.godotAnimation = godotAnimation

setAnimationTracks(loadAnimationTracks())

}

func loadAnimationTracks() -> [AnimationTrackModel] {

// Load the animation track data from Godot's Animation

// and put them in AnimationTrackModel objects, and return them

var trackModel: [XogotAnimationTrackModel] = []

for trackIdx in 0..<godotAnimation.trackCount {

trackModel.append(

XogotAnimationTrackModel(

godotAnimation: godotAnimation,

track: trackIdx))

}

return trackModel

}

// We use Godot's undo system to track any changes done to

// the models, so that the user gets undo/redo for their changes

override func setLength(_ value: Double) {

let previous = animation.length

withUndoRedoActions(name: "Change Animation Length") {

self.godotAnimation.length = value

super.setLenght(value)

} undo: {

self.godotAnimation.length = previous

super.setLength(previous)

}

}

override func optimizeAnimation() {

// Call into Godot itself to run the optimization phase:

EditorXogot.optimizeAnimation(godotAnimation)

}Xogot itself does not instantiate the base classes like AnimationModel, or AnimationTrackModel, instead it instantiates our bidirectional XogotAnimation* family off classes that can call into Godot.

Xogot currently uses about 156 observables in this fashion, it is used for almost everything you see on the screen now.

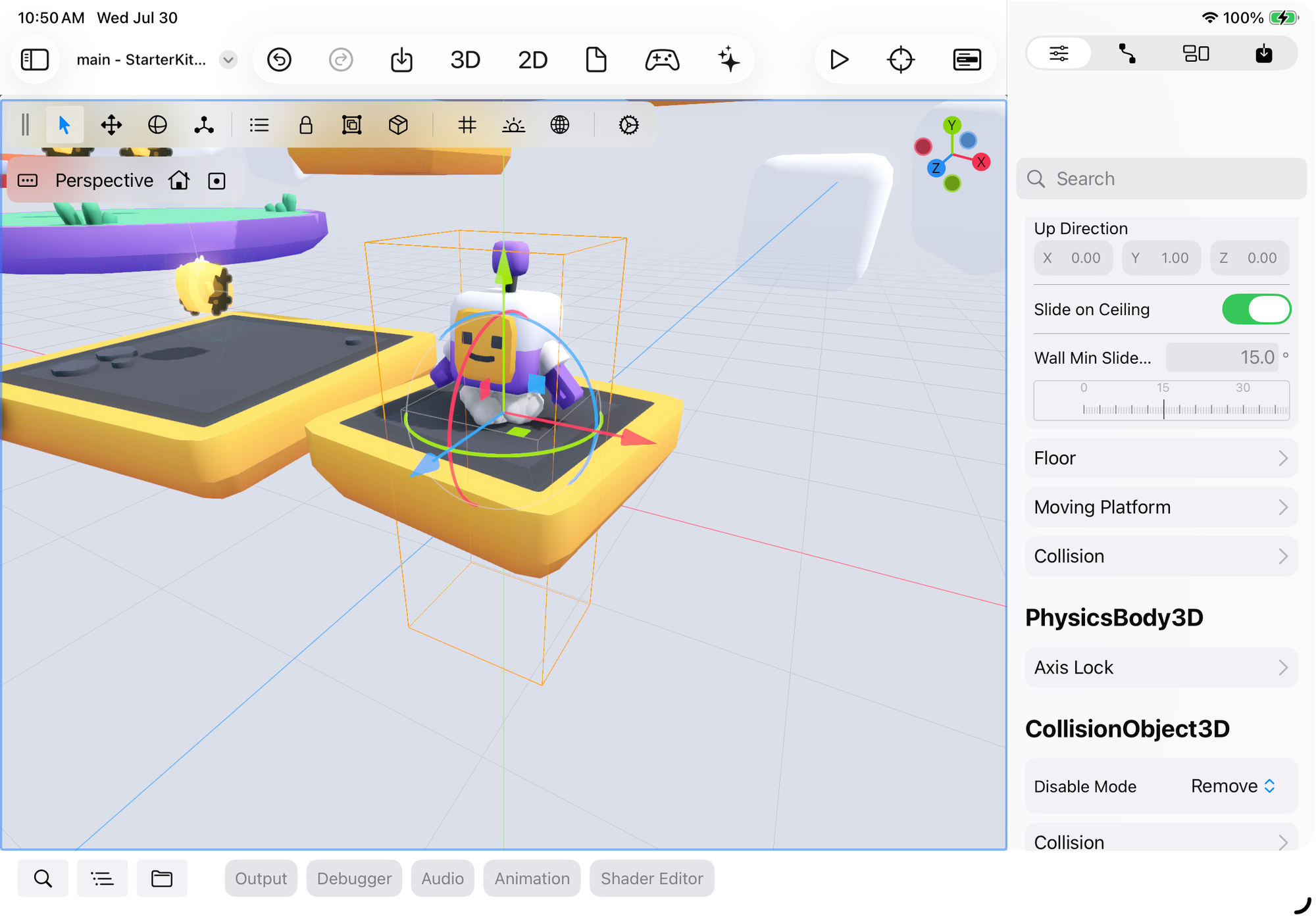

Our Shell

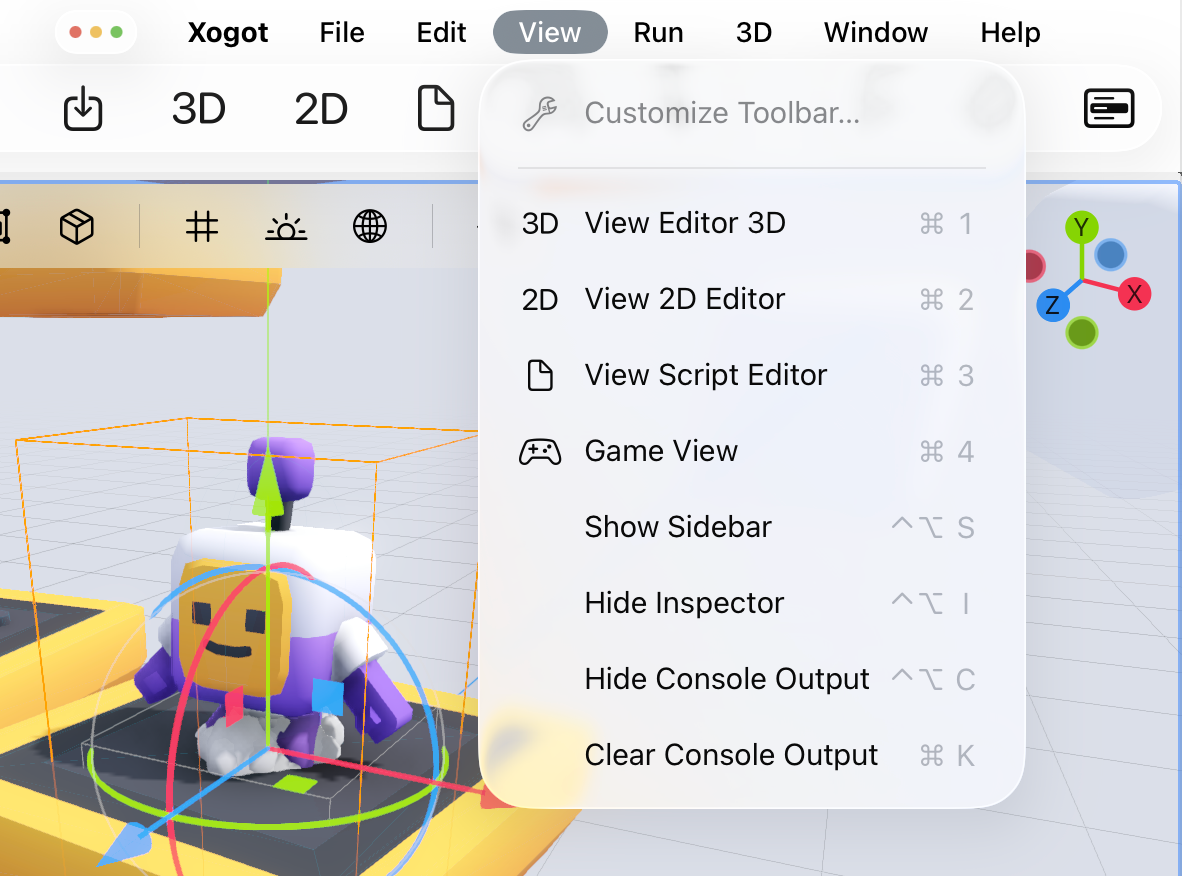

Another place where this @Observable model came up was in our editor shell:

This too started as an organic process, it was just a few SwiftUI controls wrapping Godot at first, but now we have moved entirely to a model where the shell is defined by a ShellModel class that tracks the current Godot editor, the source code editing, the plugins at the bottom and the sidebars, along with a XogotShell View that renders the model.

Like the components described before, this allows us to prototype changes to the user interface without having to launch Godot. This became more and more important as we started our work on the iPhone version and soon the Vision and Mac versions.

Not only this became convenient for these new UI elements, but having a ShellModel that we can remotely control the shell from different parts of the app was a great convenience, but also instrumental to getting our keyboard accelerators work across the whole application, as these global SwiftUI keyboard shortcuts can make decisions based on what the state of the app is.

I initially thought only a handful of users would ever get to see our cool keyboard shortcuts, as you needed a keyboard to see them (and to long-press the command key), but with iPadOS 26, swiping down from the top of the screen gives you menus, and we got them for free!

We had to do some tuning to the menus, as Apple has offered new guidance for them.

We still use @State, but purely for truly local state to a view and @Bindings in some places (extensively for showing/hiding items), but generally, our "source of truth" are now these @Observables, both the bidirectional kind as well as the 'remote control' kind.